Miss Peregrine and her Peculiar Children

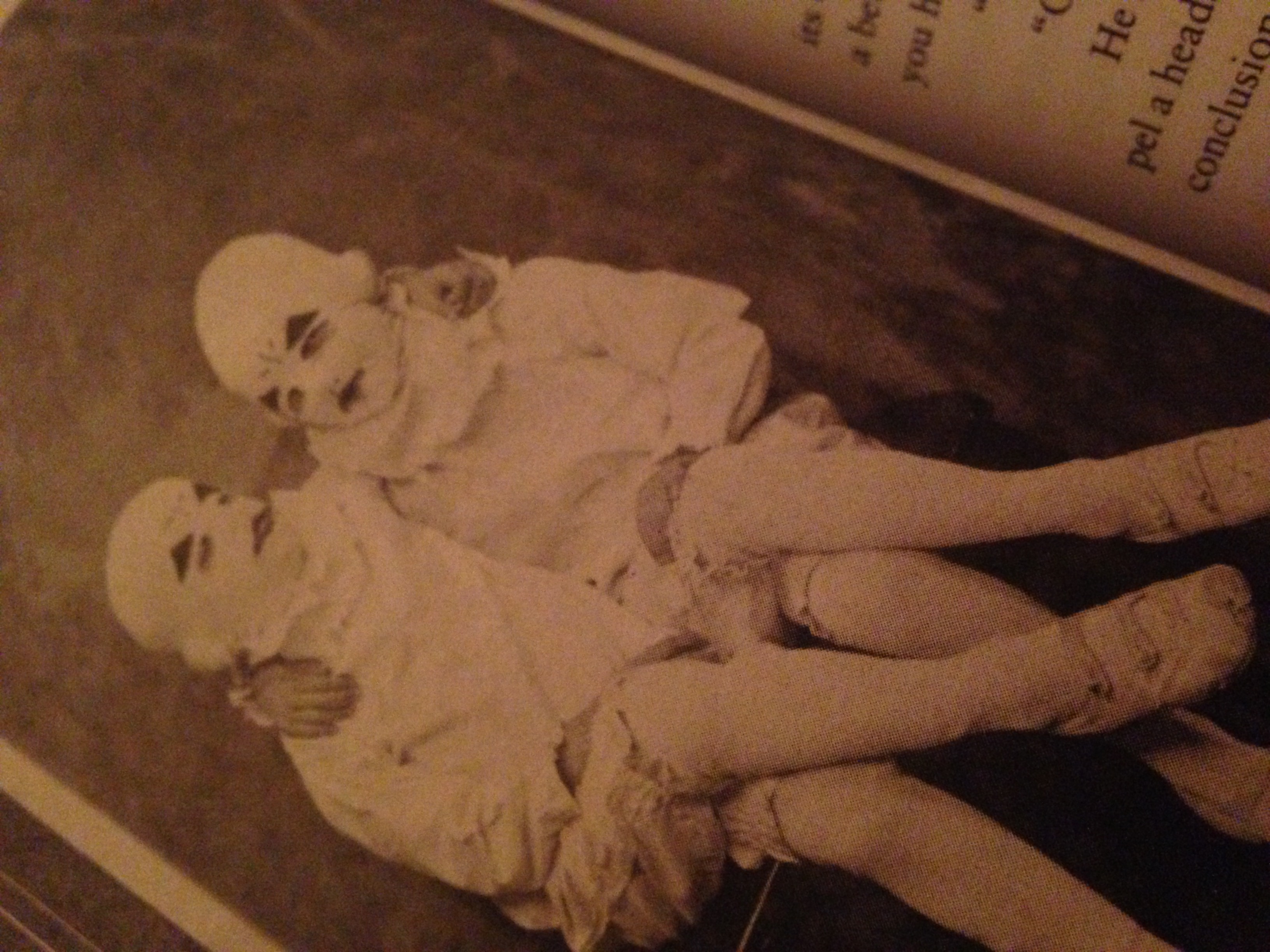

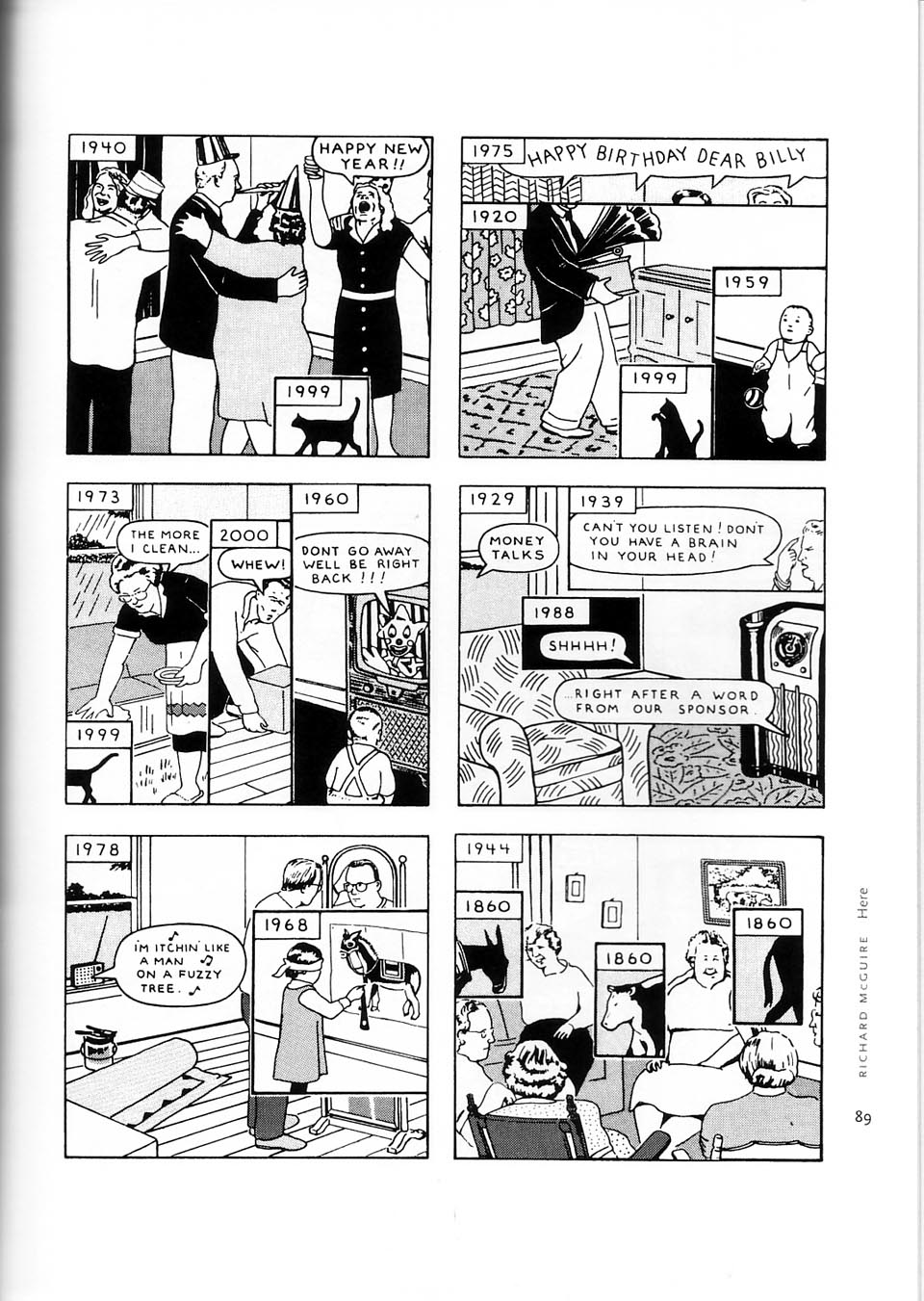

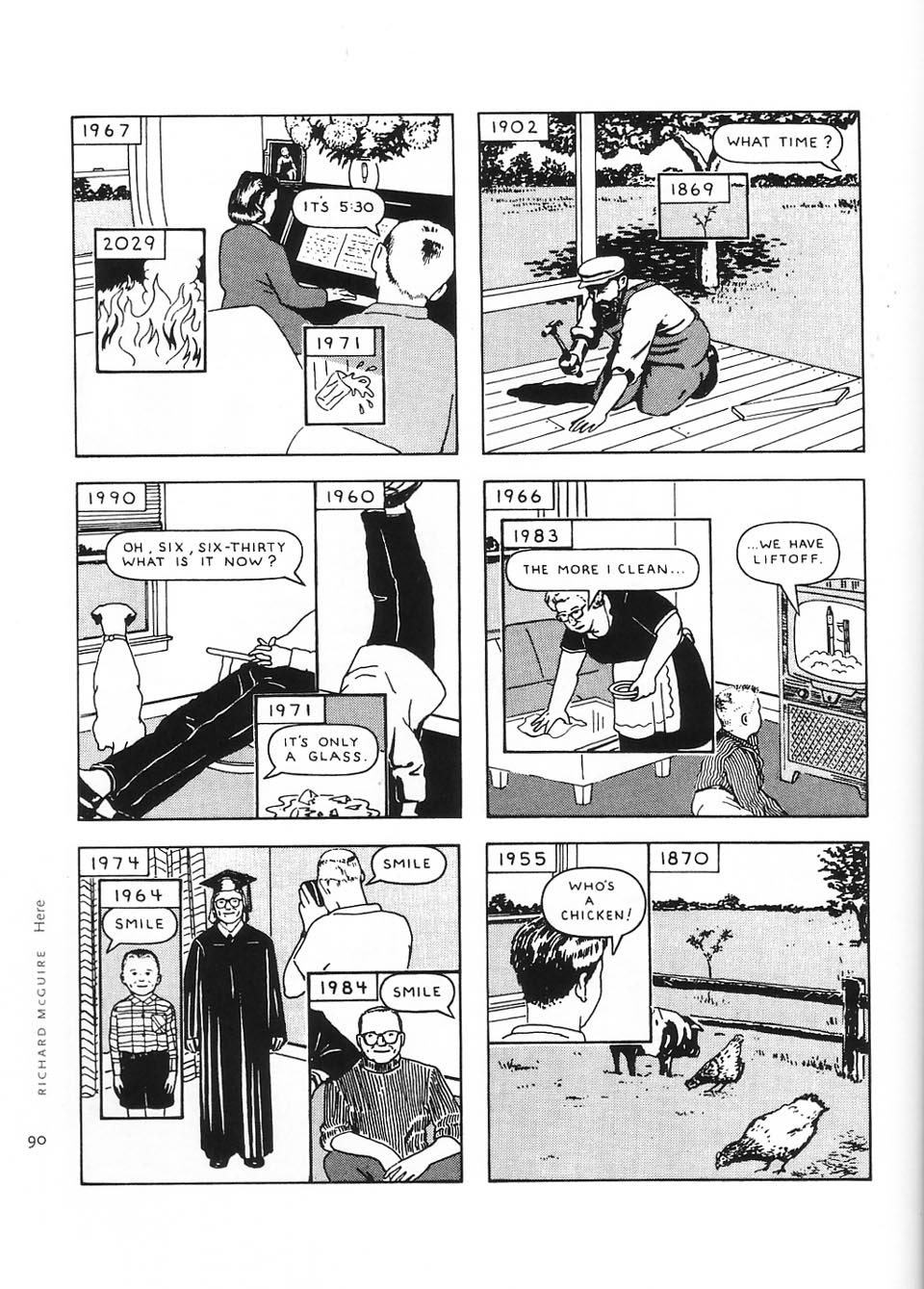

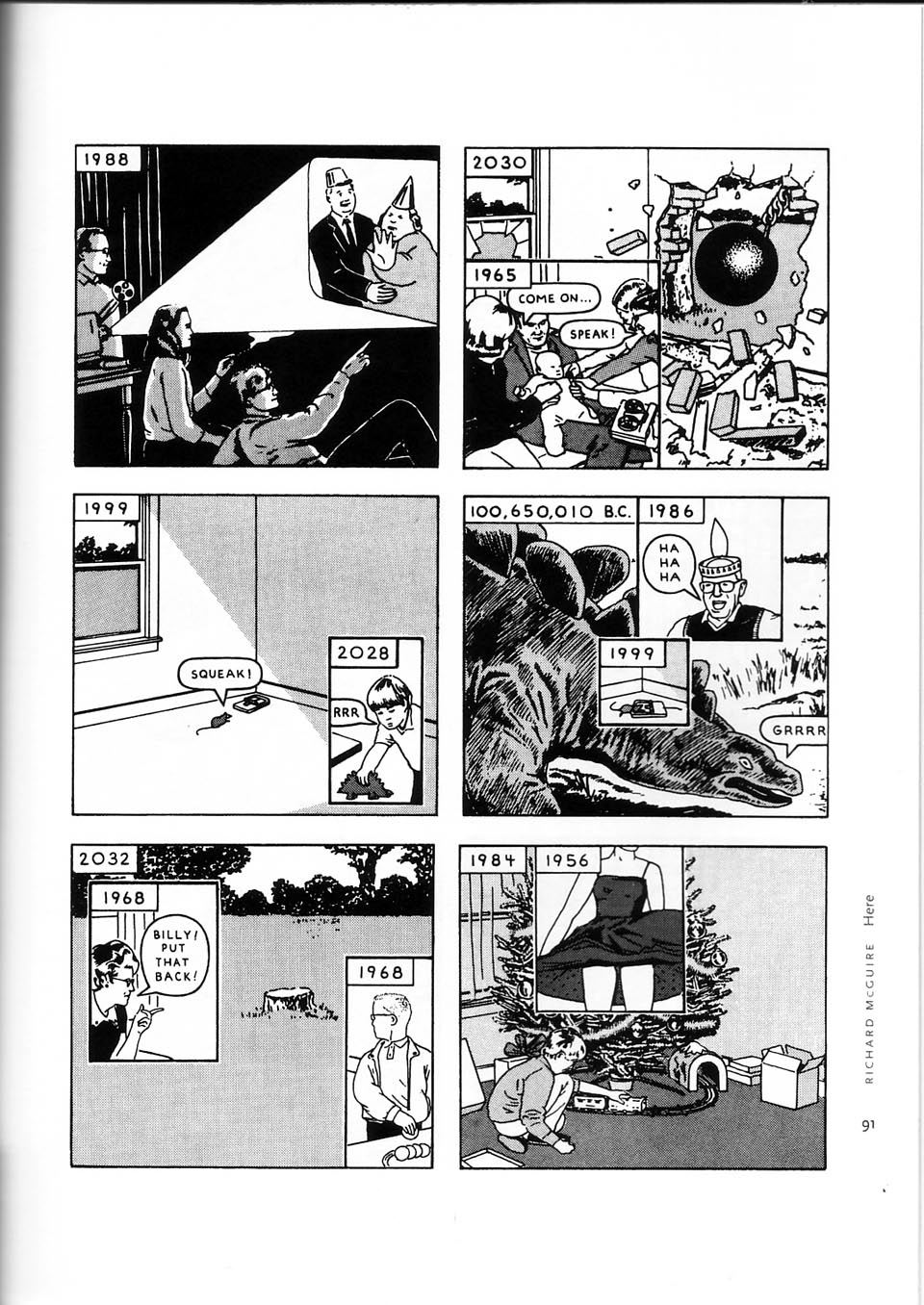

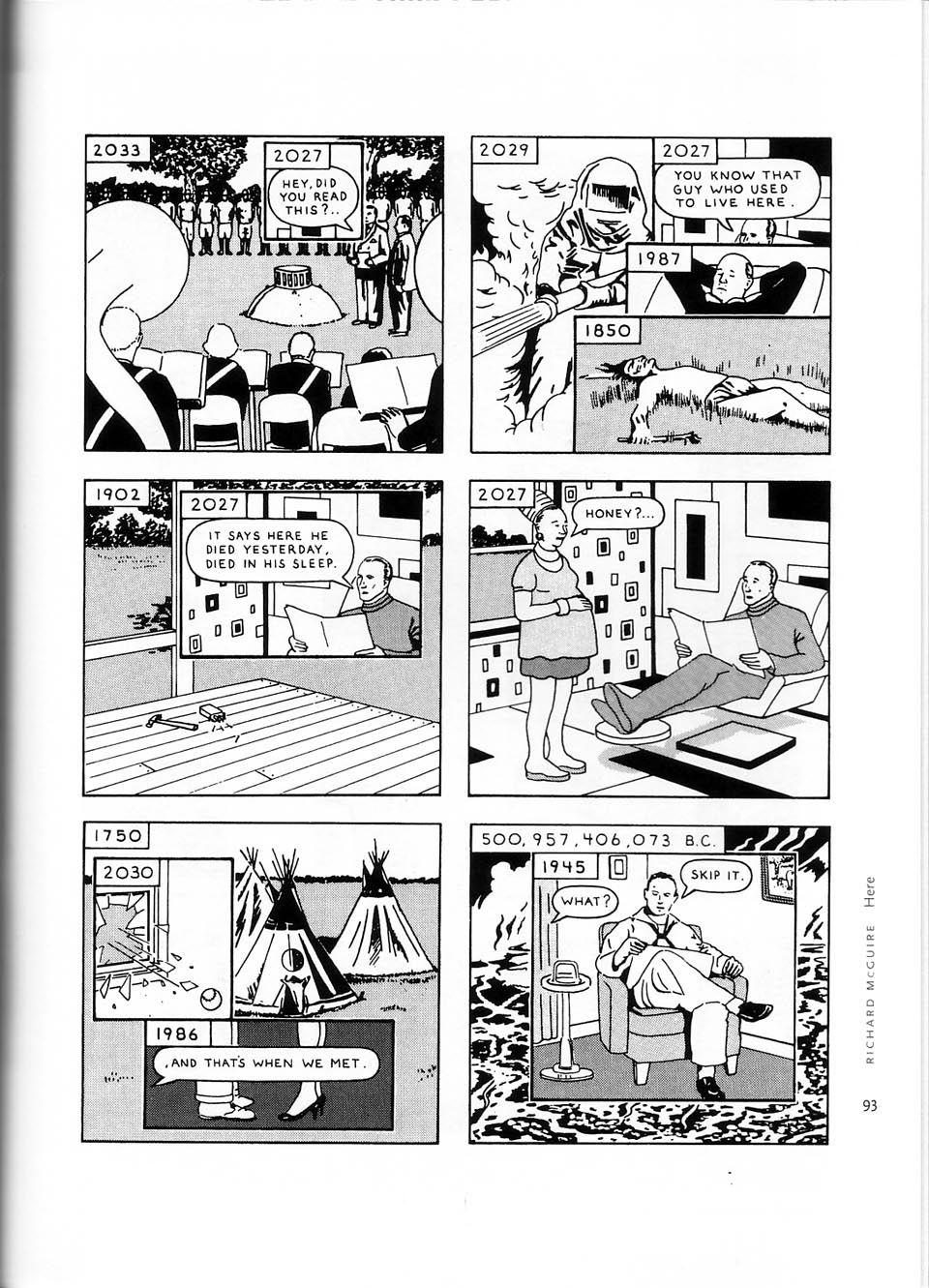

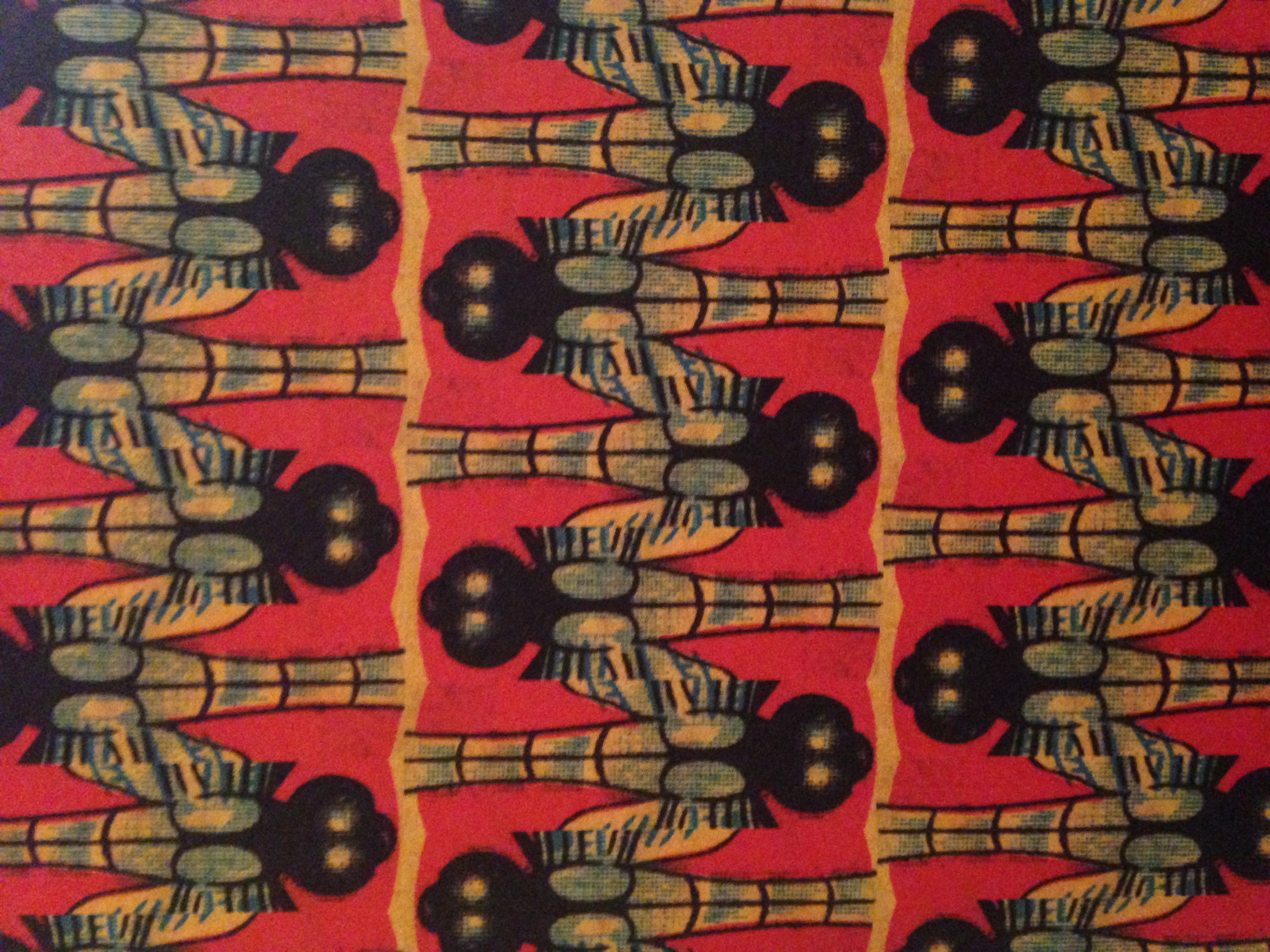

We’ve seen these old pictures before. Every holiday season they pop up on our news feeds: “15 Scary Santa Clauses”; “12 Frightening Easter Bunnies”. There’s a website devoted to awkward family photos. They’re relics of the past, the printed photograph, and separated from their history we find them alluring and almost quaint. They’re from a different time, what might as well be a different place. Though our Internet life might be drawn to images and visually centered, we see these antique photographs as something different than we might post on Instagram.

Ransom Riggs has seen these old pictures, too. Thousands of them. They’re the inspiration for his thrilling young adult series about Miss Peregrine and her Peculiar Children. Two of the three stories have been published (the final is forthcoming this fall - not soon enough) and graced the New York Times best seller’s list. There’s a movie deal. The books come with bonus material (author interviews, additional photographs). If this sounds familiar, that’s because it is. We’re used to young adult fiction series. We’re used to the movie deals. We’re used to the young adult fiction market crossing boundaries into the grown-up world.

By most markers, Rigg’s books should not be as engrossing as they are. In lesser hands, we would not care about the story being told. But Rigg’s books are not “usual.” (Aren’t you glad I didn’t say that they’re “peculiar”?) Yes, we have some traits common these days, particularly that of a story being told by an outsider to his society (or, in this case, someone who at least feels awkward and separated from his life; didn’t we all feel that way in middle school or high school?). But this isn’t a dystopian, post-apocalyptic society that we dive into. There is a matter of life and death, yes, and there is a love story, of course, but we are not amidst a rebellion or a battle to save the world from evil. We have

Riggs takes these old curious pictures and has developed a unique world from them. The premise could seem like a writing prompt from your nighttime creative writing course, and with a less imaginative mind, that’s likely what we’d end up with here: a story spun out of one picture, predictable and less fabled than the story of Miss Peregrine’s Peculiars. Riggs, however, avoids the banality that could come from this.

The story is told by Jacob Portman, a high schooler from Florida who doesn’t fit in with his classmates, coworkers, or family. After the death of his grandfather, Jacob discovers a new world filled of time loops and “Peculiars,” people with traits that range from being able to make fire, superhuman strength, being invisible, and the ability to sense the enemy, who are unseen to the normal eye. The group of “children” (who are actually older, but stuck in one of those time loops so they haven’t aged) have their world attacked by the hollowgasts and have to escape their secluded island life off the coast of Wales.

Scattered throughout the novels are these found pictures. The photos usually enhance the story. Early on, it’s clear that Riggs used the picture as an influence on a character or plot point. It is in some of these cases that I wish there were no picture. My imagination created an image, and as soon as I turn the page I see it ruined by the picture Riggs chose. But without these pictures, we wouldn’t have the characters or the story. As we get into the second book it becomes less clear that the picture influenced the words. He has stated as much, saying that in the second book he looked for pictures to meet his story more than looking for a story to meet his pictures. The design of the books is well-done, though the inclusion of pictures always necessitates a full page, thus leaving a lot of blank space at the end of paragraphs.

The Peculiar Children do not survive without their fair share of deus ex machina, but that’s common in these types of novels. Only once did I find it to be trite. Riggs handles the plot twists with ease. The suspense of the tale only slackens during the teenage love scenes and some interior monologues from Jacob, our fair narrator.

I devoured both of these books in a few days. That’s a testament to their energy and drive and the sweeping storyline. I’m eagerly awaiting the third book’s appearance in the fall.

(Miss Peregrine's Home for Peculiar Children finished April 4, 2015; Hollow City finished April 10, 2015)